By Paskorn Jumlongrach

The recent destruction of KK Park and the rapid crackdown on scam enclaves in Shwe Kokko have raised pressing questions along the Thai-Myanmar border. On the night of 17 November, Colonel Chit Thu, long-time commander of the Karen Border Guard Force (BGF), ordered the demolition of hundreds of buildings inside KK Park. Within hours, what had been one of the region’s most notorious criminal hubs had fallen silent. His forces then moved deeper into Shwe Kokko, prompting panic among Chinese “dark” and “grey” operators who had run the area for years, and among the countless trafficked workers trapped inside. Many fled in confusion, unsure whether this was a genuine law-enforcement operation or a political manoeuvre.

The most urgent question now is simple: what powerful pressure drove Col Chit Thu to dismantle the very strongholds that had long sustained his influence? Pressure from the Myanmar military alone does not fully explain such a dramatic reversal. The BGF’s rise over the past decade has been fuelled by revenue from Shwe Kokko, KK Park and related illicit economies. With an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 fighters on its payroll, the BGF is now one of the strongest non-state forces along the border. Its salaries and benefits outclass those of other Karen factions, leading to a situation where fighters from poorer Karen forces sometimes “park” their men with the BGF simply because it can afford to support them.

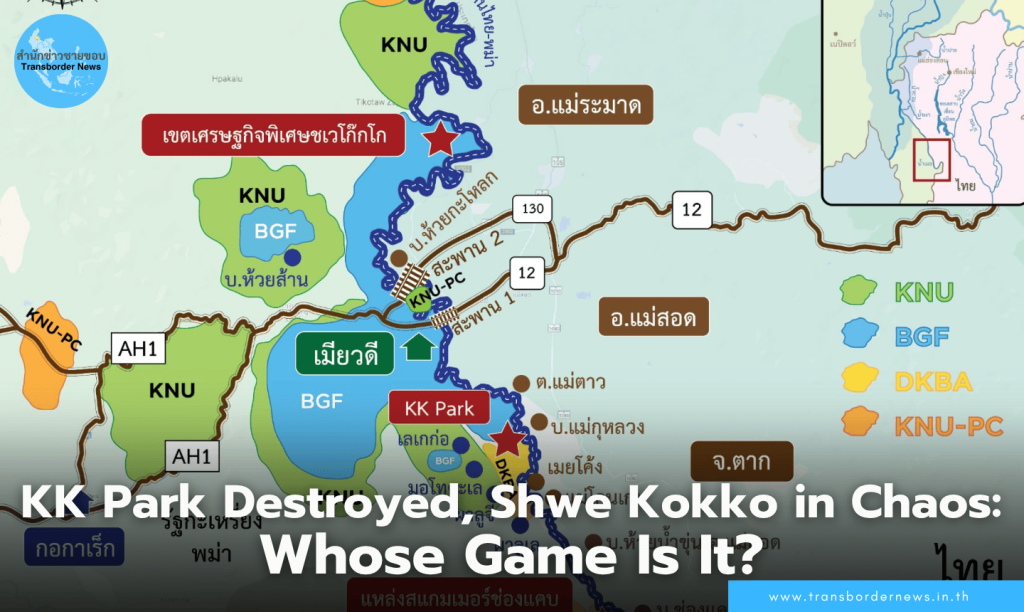

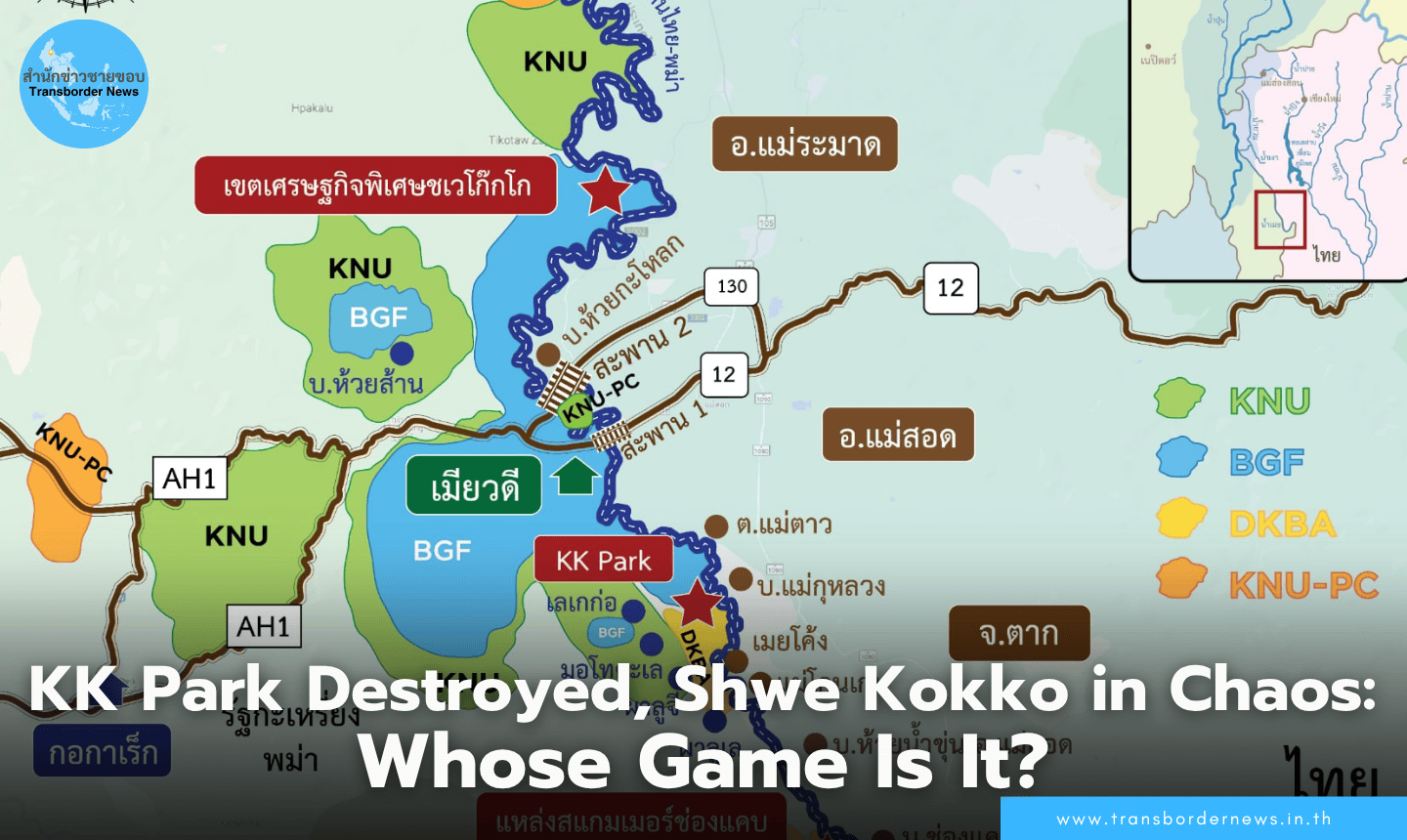

The BGF did not start out this way. It emerged in 1994 as a splinter from the Karen National Union (KNU), accusing KNU leaders of Christian domination. Led by Chit Thu, the breakaway group allied with the Myanmar military and helped overrun the KNU’s headquarters at Manerplaw. Under the 2010 junta-drafted constitution, the group was formally incorporated as the Karen Border Guard Force. Yet despite its allegiance to the Myanmar military, Chit Thu maintained warm personal ties with certain KNU leaders, allowing him to operate in the political “grey” zone between warring sides. This delicate balancing act enabled the rapid establishment of Shwe Kokko as a special economic enclave and later the explosive growth of KK Park, including on land associated with the KNU.

Equally important were Chit Thu’s connections inside Thailand. He cultivated durable relationships with local officials, business interests and even national-level patrons. Benefits flowed in both directions across the narrow Moei River. These arrangements help explain why major world powers have sanctioned him, yet Thailand has never issued an arrest warrant and his financial networks appear to remain well-protected. Against this backdrop, the sudden destruction of his own empire raises even more questions.

Some observers initially suspected theatre—a staged performance by the junta and the BGF aimed at showing “progress” before regional meetings and Myanmar’s planned elections. Others believed Chit Thu was using the moment to weaken internal rivals, particularly Tin Win, another influential BGF commander who controlled parts of KK Park and whose growing ties with the Democratic Karen Benevolent Army (DKBA) may have been seen as a threat. If KK Park had come to serve Tin Win’s networks more than Chit Thu’s, demolishing the buildings could be a strategic reset.

But the scale of the operation, and the fear it triggered, suggests that a deeper force is at work. It is possible that Beijing applied pressure on the junta, which in turn leaned on the BGF. China has signalled growing concern over transnational scam syndicates operating along the border, many of which traffic Chinese nationals. It is also possible that transnational crime networks themselves have decided to relocate to safer territory, sensing that Shwe Kokko and KK Park had attracted too much attention. Meanwhile the DKBA is reportedly preparing similar operations to clear out scam centres in its territory, further adding to speculation that several Karen armed groups may be reacting to the same external pressure.

Geography has long shielded these enclaves. Shwe Kokko and KK Park sit immediately across from Mae Sot, separated only by the river. Any unilateral attack by the Myanmar military risks incidents with Thailand. In addition, the BGF controls Myawaddy town, while surrounding areas are held by the KNU. A junta assault without BGF cooperation would trigger battles not only with thousands of BGF fighters but also with KNLA and People’s Defence Force units, who remain hostile to military rule. To this already tangled battlefield, one must add China’s interest in cleaning up cross-border crime, US concerns over Myanmar’s rare-earth trade, and Russia’s growing footprint in Dawei’s energy sector. Every external power has its own stake in what happens along this narrow riverbank.

Thailand’s response so far has been disappointing. When Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul visited Mae Sot recently, he appeared confined to the limited briefings provided by local officials. He made no substantial mention of corruption, even though he was standing in one of the largest hubs of illicit revenue in the country. More troubling was his failure to distinguish clearly between trafficked victims and actual scammers. Rather than collecting intelligence from rescued victims—as China and other countries consistently do—he focused on rapid repatriation. This approach forfeits critical opportunities to dismantle criminal networks that rely heavily on Thailand’s banks, telecom providers and logistics routes.

Neighbouring countries are now moving aggressively to dismantle their criminal enclaves. Thailand should be benefiting from this regional clean-up. Instead, by refusing to address its own entrenched interests, it risks becoming a more attractive haven for the very networks being pushed out of Myanmar. The “grey” economy that once sat across the water may gradually seep into Thailand’s opaque bureaucratic layers if no decisive action is taken.

Unless Thailand is willing to examine its own institutions, confront its own protectors of the trade, and dismantle the systems that have long enabled illicit enrichment, the country risks emerging not as a stabilising force in the region but as one of Southeast Asia’s most prominent grey-zone states.

This is a translation of original Thai op-ed https://transbordernews.in.th/home/?p=44461

transbordernews.in.th