By Paskorn Jumlongrach

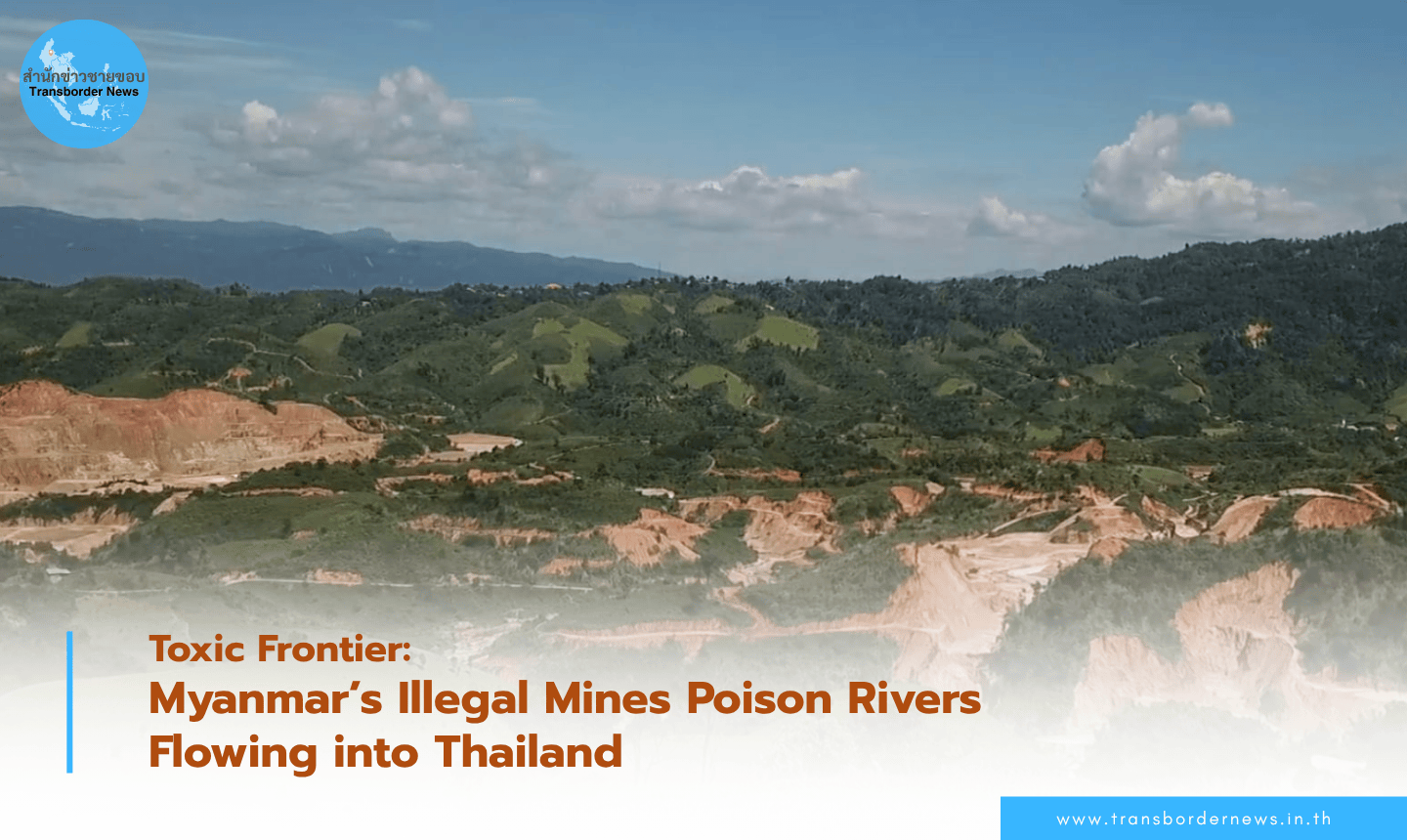

At the top of Doi Hua Mae Kham, a mountain rising 1,850 meters above sea level in northern Chiang Rai, the border between Thailand and Myanmar is little more than a ridge of red earth and grass. From here, one can look across into Myanmar’s Shan State and see vast scars of exposed soil — open-pit mines glinting under the sun, some no more than a few kilometers from Thai soil.

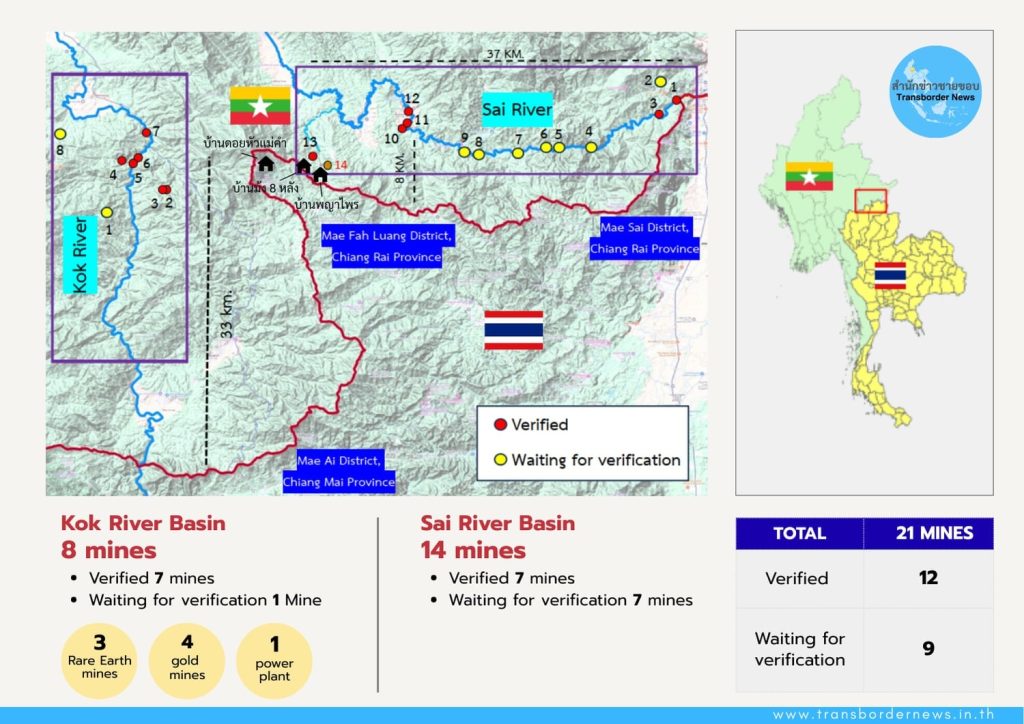

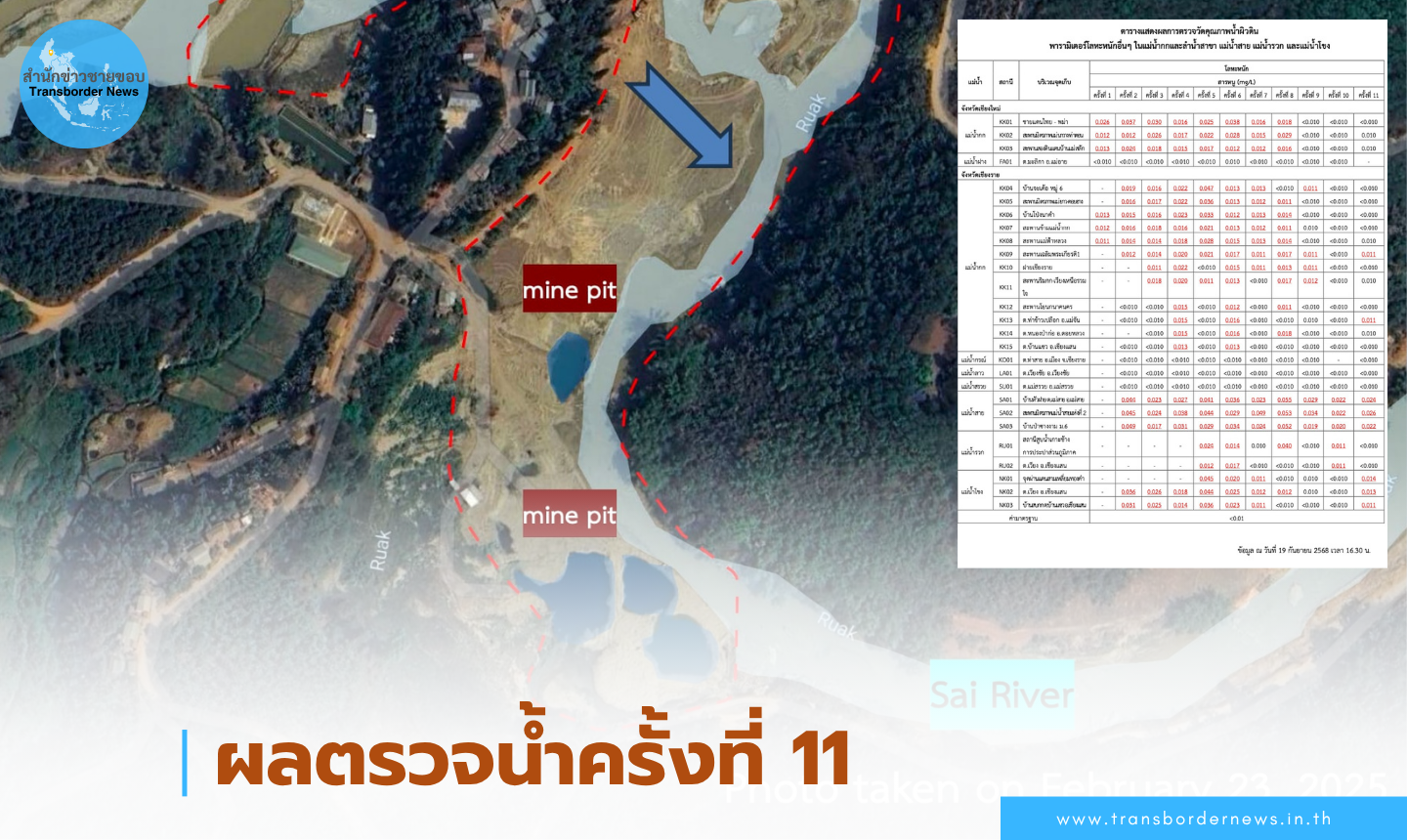

These mines — gold and rare earth — have multiplied in recent years, eating into the mountains that cradle the Kok and Sai rivers, two tributaries of the Mekong. From the Thai side, they are easy to see. But on paper, they barely exist.

“They’ve been digging for about five or six years,” said a Hmong villager from the small settlement known as Ban Hmong 8 Houses, which sits on the winding road toward Hua Mae Kham. “Now they’re expanding closer to us. There are Chinese workers, trucks moving all day and night, and Lahu soldiers guarding the area. No one from outside is allowed in.”

The mine he refers to is known locally as “Mae Jok,” part of Tachileik District in Shan State. According to Thai security sources, it covers roughly 1.8 million square meters — over a thousand rai of land. A check on Google Earth confirms the open pits and a cluster of turquoise ponds typical of rare earth processing.

Both sides of this border are under watch. To the east, Myanmar’s military has bases scattered across the Sai River basin. To the west, the United Wa State Army (UWSA) controls the highlands that form the headwaters of the Kok River. The two armed groups have long divided their areas of influence, with the Thai border serving as a tense but quiet boundary.

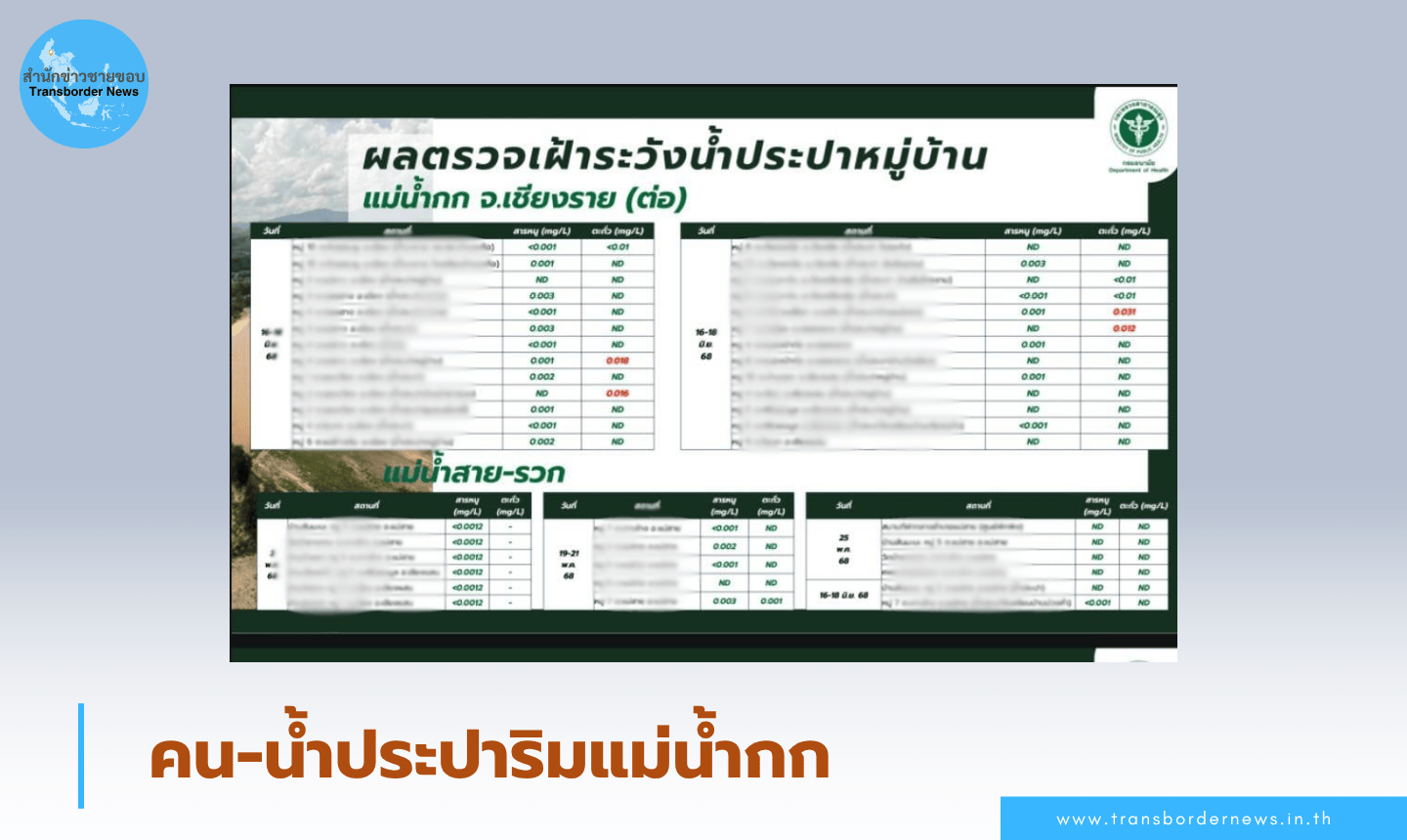

For communities downstream, however, the cost of that arrangement is rising fast. Sediment and chemicals from unregulated mining flow freely into streams and tributaries that feed the Sai River.

“This used to be forest,” another villager said, pointing to patches of scrub and stumps where large trees once stood. “Now it’s just bare hills. That’s why Mae Sai floods — the mud and runoff come from there.”

In September 2024, flash floods and mudslides hit Mae Sai, inundating neighborhoods and destroying homes. Local volunteers suspect the torrent was fueled by deforestation and mine runoff from across the border. No official investigation ever traced the source.

Further west, the same story repeats along the Kok River. At least seven mines — gold and rare earth — now operate near its upper reaches inside UWSA territory. The area was hit by similar landslides and river pollution in September 2025, choking the river with thick, red mud.

Despite the visible damage, Thai authorities have been slow to respond. Cross-border cooperation mechanisms with Myanmar, both local (TBC) and regional (RBC), have stalled amid the post-coup turmoil and military control of border areas. Myanmar officials have claimed they cannot enforce laws inside UWSA territory — a claim that Thai observers dismiss as an excuse.

“Millions of people in northern Thailand are living with the consequences of cross-border pollution,” said a Chiang Rai–based environmental advocate. “These rivers are part of the Mekong system. If the contamination continues, it could become one of the world’s largest transboundary pollution crises.”

For villagers on the border, the threat is more immediate — and more personal. The forest that once protected their farms is gone. The river that sustained them now runs cloudy after every rain. And just across the ridge, the sound of machinery never stops.

This is a translation of original Thai article https://transbordernews.in.th/home/?p=44048